|

Department of Environment and Resource Studies A DECISION-MAKING MODEL FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF VEGETATIVE ECOSYSTEMS IN PROVINCIAL PARKS Senior Honours Thesis By: Oliver K. Reichl, 87261160 Submitted: April, 1989. For: ERS 490A and 490B Advisor: Dr. George Priddle FOREWORD A few years ago, someone in the Pinery Provincial Park's management hierarchy decided that this very popular park would look better if it again were stocked with towering White Pine. The park proceeded to plant thousands of young trees (implying many man-hours and great cost). The pines grew well, in the process creating more and more shade. Coniferous forest was succeeding field vegetation, including lupines. This same park contains an area that is one of five (and is the largest of them) sites in the world for the Karner Blue Butterfly, whose larva feeds on lupine. In a stoic attempt to make the park more aesthetically appealing to its tens of thousands of visitors, the Karner Blue's habitat was being destroyed. Park staff are now in the process of removing many of these pines and are planning a prescribed burn so that lupine can re-establish itself. This involves still more man-hours, questions the credibility of the ministry, and will sacrifice some of that sought-after aesthetic value. Had successional trends been incorporated into the initial decision-making process, much of this could have been avoided. Based on this experience, one can make inferences towards the value of habitat diversity, the costs of not considering long-term effects, and that there is a need for a management model that helps park managers avoid such costly errors in decision-making. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to thank the following for their time, advice, and invaluable assistance: Tom Beechey, Life Science Resource

Planner, Parks and Recreational Areas Branch, MNR, Toronto. TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES [Top]

INTRODUCTION [Top] Ontario will, as of May, 1989, have 270 provincial parks and park reserves, many with their own managerial staff (OMNR, 1988). Barely a quarter of them have master and/or management plans (Beechey, 1989). This means that many superintendents are not operating their parks with clear directives particular to their parks. Ecology has been defined as the "totality or patterns of relations. between organisms and their environment" (Webster's Unabridged Dictionary), or as "the biological study" of this totality (Hill, 1969; Smith, 1980). This 'environment' includes land, air, water, and other organisms, including humans. Park management, when executed effectively, is based on ecology, but relies largely on advances in certain areas of biology (eg. wildlife) and, more recently, environmental (eg. impacts of outdoor recreation) and behavioural (e.g. wilderness perceptions) studies. The park manager must know more than the dynamics of fish and wildlife populations, geomorphological changes, and societal values. Park management begs holism. It is more than resource management, whether that resource is abiotic, biotic, or cultural. It is also the management of the inter-relationships among them. There has been little application of ecosystem concepts to park management at the field level (Priddle, 1988; Eagles, 1989; White, 1989; Francis, 1988; MacPherson, 1989). This is partially because of limited ecological affluence among park managers (MacPherson, 1988; Eagles, 1989). It may also be attributed to the use-oriented values of the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR). If park managers do not have a strong ecology background to supplement their administrative skills, decisions made regarding the management of their parks are often myopic, do not apply ecosystem concepts, and are not considered holistically and in light of the stability and sustainability of the ecosystem(s). A park manager who fails or refuses to recognize the importance of a holistic, ecologically sound decision-making process is ill-equipped for her/his position. Park managers need a management model that helps ensure decisions consider ecosystem concepts and are made with long-term sustainability in mind. Before such a model can be applied, however, it may be necessary for park managers to upgrade their level of competence in terrestrial and aquatic ecology. This paper will concentrate on terrestrial ecology, with an attempt at applying the concept of vegetative succession. In Section 1, the park system, its planning process, the ministerial and park administration structures, and policy are reviewed briefly. Institutional obstacles that have prevented the application of ecosystem concepts, responses to these obstacles, and some new avenues are discussed in Section 2. In Section 3, it will be shown that the model can be applied regardless of institutional hindrances, and without departing from existing systems. This is accomplished by delineating explicitly the value system needed for its success. If ecological factors are considered at the top level of decision-making, they can have a highly positive influence (Myers, 1984). The model must otherwise be flexible. It must be precise enough to help manage unique situations, yet general enough so that it can be applied ubiquitously. PART I - TOWARDS A MODEL

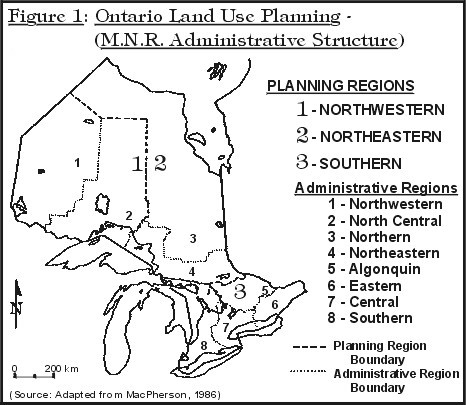

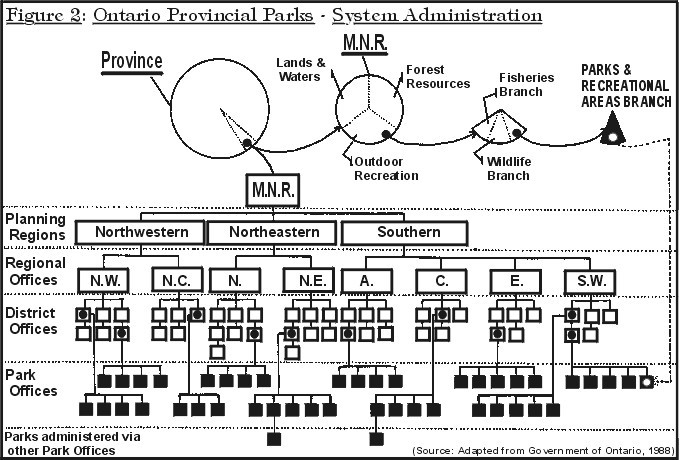

The provincial parks system in Ontario began in 1893 with the inception of Algonquin Park (Miller, 1985). Today the system boasts 217 parks, with. 53 more to be added by May, 1989 (OMNR, 1988). Once these 53 parks have been added, approximately 6.3 million hectares (6%) of Ontario's land and water base will be represented (OMNR, 1988). Many of these parks are only reserves; that is to say that they exist via regulation under the Provincial Parks Act (R.S.O., 1980), they are not developed, and will only gradually be brought 'on-stream' as demand becomes evident. The provincial parks are administered by the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) which came into existence under the Ministry of Natural Resources Act, 1972 (Reichl, 1987). In the broadest scope, the MNR's goals focus on resource development, resource conservation, and the protection of public safety and resources from natural hazards. The MNR's programmes are based on a concern for the wise management of Ontario's physical resources; wise management for both economic and social benefit (Reichl, 1987). Presumably, once any measure of economic and social benefit is achieved, environmental/ecological benefits are realized as well. To aid in the achievement of its goals, the MNR solicits assistance from federal departments and other ministries, and offers technical advice and extension programmes to municipalities and the private sector. In recent years the MNR has encouraged increased involvement from private industry and the general public towards achieving its goals (Reichl, 1987).  The MNR has two 'sister-levels' of organization. Geographical coverage is achieved by three planning regions made up of eight administrative regions (See Figure 1). Responsibilities are divided into three broad groups: Forest Resources, Outdoor Recreation, and Lands & Waters. The provincial parks system is administered through the Parks and Recreational Areas Branch of the Outdoor Recreation group (See Figure 2).  The main MNR planning document for its provincial parks is Ontario Provincial Parks: Planning and Management Policies, also known as "The Blue Book". This manual describes the goal of the provincial parks as providing "a variety of outdoor recreation opportunities and to protect provincially significant natural, cultural, and recreational environments" (OMNR, 1978). This goal is realized by four objectives: protection, recreation, heritage appreciation, and tourism (OMNR, 1978).

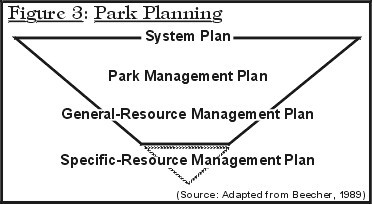

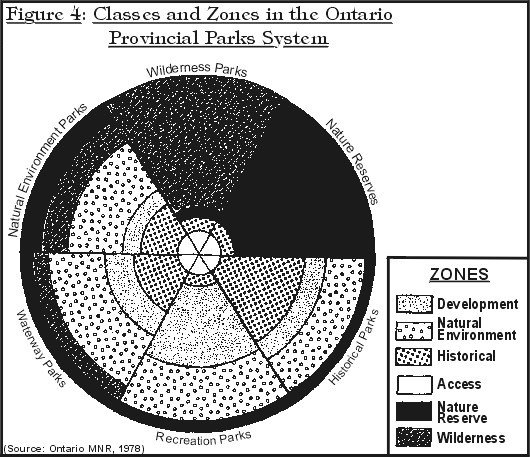

As of May, 1989, the Ontario provincial parks system will consist of four historical parks, 31 waterway parks, 76 recreation parks, 67 natural environment parks, eight wilderness parks, and 84 nature reserve parks (OMNR, 1988). Since approximately 1975, funding to the Parks and Recreational Areas Branch has remained more or less static (Beechey, 1989; Eagles, 1989). Along with this virtual freeze on funding came a major deceleration of the master and management planning process in the early 1980's despite the creation of the Blue Book in 1978. The need for increased activity in this area was recently recognized with a streamlined resurgence of park planning. Master plans, once thick documents that preceded only slightly leaner management plans, are no more. Management plans themselves are also more streamlined: The Pinery Provincial Park Management Plan 1986 is a manageable ten pages. Eighteen management plans for various parks are presently being prepared (Beechey, 1989). These plans, plus existing ones, may be supplemented by resource management plans specific to life and earth science or cultural resources (See Figure 3). These are a new dimension to the planning process, and none have been approved as yet (Beechey, 1989). Some parks may reveal a need for resource management plans specific to one particular resource (e.g. deer, Pitch Pine, Karner Blue).  Parks are classified according to the six categories mentioned earlier. These six classes, in principle, provide the range of opportunities and degree of protection that the people of Ontario desire. The classification is based on several guiding principles that reflect the MNR's prime directives. Some of these are representation (of natural or cultural features), variety (based on the Recreation Opportunity Spectrum), coordination (with private and other public agencies), and zoning (Ward and Killham, 1987). Zoning within a park furthers the objectives of the system by designating nature reserve, development, historical, access, natural environment, and/or wilderness zones within each park (See Figure 4). Zoning is the result of an allocation of recreational, natural, and cultural values to portions of a park. Special 'resource utilization' zones exist in Algonquin and Lake Superior Provincial Parks to permit logging (OMNR, 1988).  Ecosystem concepts should ideally be applied in all classes and zones, but they are particularly important to Wilderness, Natural Environment, and Nature Reserve parks and zones, for it is here that the stability and sustainability of ecosystems is most vital for maintaining the values allotted to them.

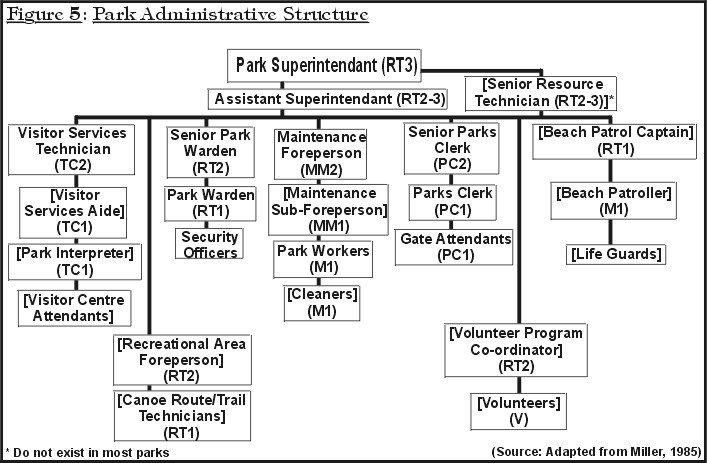

Natural Environment parks "incorporate outstanding recreational landscapes with representative natural features and historical resources to provide high quality recreational and educational experiences. They contribute to the achievement of all four objectives of the system and are also the essence of the provincial park ideology, as they incorporate all the values for which the system stands (OMNR, 1978). By incorporating all the values of the system and offering this values spectrum through policy to the manager, Natural Environment parks become the most likely arena for conflicts resulting from the protection vs. use dichotomy (Reichl, 1988). They are also among the most popular parks in the system (e.g. Algonquin, Pinery, Presqu'ile, Bon Echo, Sandbanks, Sibley, Rondeau, Killbear). Each provincial park is under the control of the Minister and under the charge of a district manager and superintendent designated by the Minister. The Minister has the latent authority of the Crown to manage all public land in the province (Eagles, 1989). The Provincial Parks Act (R.S.O., 1980, c401, s7(1)) transfers this authority to the district managers and superintendents, giving them up to 100% decision-making power within the park boundary (Eagles, 1989; MacPherson, 1988; Peck, 1987; Sargant, 1987b). The Blue Book (and the management plans, if they exist) offers the superintendents guidelines (i.e. values) for managing their parks.  If the superintendent has good downward communication skills, (s)he will transmit these values to all other park staff (See Figure 5). In the performance of their tasks all staff transmit this value system further, often to the park visitor. Interestingly, only one of the positions in any park administrative structure, that of Senior Resource Technician (SRT), has resource management responsibilities written expressly in the description of duties (Note: presently, only Sandbanks and Presqu'ile have SRTs; both Sandbanks and Presqu'ile are Natural Environment parks). More intriguing, however, is that many positions are classed on the technical level (RT-Resource Technician) and often held by people with a largely technical background (Eagles, 1989; MacPherson, 1988). 2. DISCUSSIONS ON APPLYING ECOLOGY

Before developing a management model that incorporates an ecosystem concept, it may be useful to discuss the larger system in which it will be applied. One aspect of researching this paper involved talking with park staff, former park staff, academia, and park planners to get input towards the development of the model. Rather than resulting in a collection of ideas that could be incorporated into a model, these discussions produced a list of criticisms about the system that essentially address the question of why ecological considerations are rarely included in the decision-making process. While there was unanimous agreement on the need for such an inclusion, there was a variety of obstacles mentioned that have, among other things, hindered the application of ecosystem concepts. There have been responses to some of these obstacles (not necessarily in light of applying ecology), with various consequences, as well as other avenues that could be pursued (See Table 1). All of these will affect the successful application of succession to park management. Table 1: Obstacles, Responses, Consequences and Avenues [Top]

(Source: Adapted from MacPherson, 1988; Eagles, 1989; OMNR, 1981, 1988; Sargant, 1987; Francis, 1988; Whillans, 1989; Priddle and Nelson, 1982; White, 1989; Reichl, 1987, 1988; Bird and Rapport, 1986)

(Deputy Minister, MNR, to the Provincial Parks Council; from Priddle, 1988) One strong sign of concern about the adequacy of current management has been the call for the relocation of parks to a less extractive-oriented ministry (Priddle and Nelson, 1982). The MNR has been likened to a fox, with parks as chickens (Priddle, 1989). This view underlines the concerns for protection and preservation articulated by many academia, park staff, and the general public. The observations are quite understandable given that the MNR's prime directives are all based on utilitarian values. Even the more specific objectives of the parks system outnumber protection three to one. Compare also the goal of the provincial parks system with that of national parks: "Ecological and historical integrity are Parks Canada's first considerations and must be regarded as prerequisites to use." (CPS, 1980). A utilitarian value-orientation has several implications, two of which include potential threats to the ecosystems, and the assessment of goal-achievement being largely done in terms of use (i.e. revenue). Such an assessment led to the contracting out of some entire parks in the early 1980's, to help them become profit-yielding enterprises (MacPherson, 1986). The MNR stresses that parks can not be all things to all people (Beechey, 1989; White, 1989). Perhaps one ministry can not be all things to all parks.

Presently, park managers are encouraged to recognize the value of "significant" resources via policy and management plans. Ecological concepts (e.g. habitat, niche, succession) are not formally incorporated in the management function. For example, habitat value was superceded by commercial value (for mining) in designating the boundaries to Polar Bear Provincial Park. Park management includes managing the inter-relationships among resources. To the park manager, awareness of these inter-relationships is as important to managing park ecosystems as social relationships (e.g. friendships, cliques) are to managing personnel. By simply designating a particular resource as "significant", the traditional park manager is steered away from the remainder which must be "insignificant". The manager of inter-relationships, on the other hand, may expend more effort towards managing particular resources, but does not justify this in terms of significance, because there is nothing insignificant in an ecosystem. While one frequently mentioned obstacle was limited ecological expertise at the park level, it should be stressed that professionalization may not be imperative for all classes (Beechey, 1989). There was some consensus, however on the need to do so in Wilderness, Natural Environment, and Nature Reserve parks (Beechey, 1989; MacPherson, 1989; White, 1989).

Park zoning is not always commensurate with biological communities (that shift with successional changes); nor are park boundaries. This becomes particularly important when nature reserve zones are at a park boundary, like at the Pinery. One of these zones, designated to protect the habitat of a very rare butterfly (recall Foreword), became a victim of pesticide drift in the summer of 1988 when the Ministry of Transportation and Communications responded to local complaints of tent caterpillar infestations by spraying malathion, a contact insecticide, along the road allowance adjacent to the park (Whillans, 1989). Ironically, this occurred in late July when the caterpillars had long completed the active stages of their life cycles. This is not only a symptom of entomological ignorance and amateur pest control on the part of the MTC, but also a sign of poor inter-ministerial communications, and exemplifies the need for buffer zones around parks. Buffer zones have been identified for some parks, but this has yet to be acted upon (Beechey, 1989). This is due in part to the fact that the MNR is only 'one voice in many' where land use planning is concerned, and the MNR has little ability to 'strong-arm' municipal government (Beechey, 1989). Many of these obstacles are beyond the control of the park manager, though this does not necessarily imply that an ecosystem management model cannot be applied. The Provincial Parks Act provides for the opportunity: superintendents have the full authority of the Minister within the park boundary. PART II - MANAGEMENT BY SUCCESSION

The application of ecosystem concepts is necessary to help ensure the stability and sustainability of ecosystems. A model, or decision-making framework, can facilitate this imperative. There are six classes of provincial parks within which such a framework can potentially be deployed, and there are many concepts (eg. food chains/webs, autotrophism, hydrophytes) that need to be understood prior to such deployment. This section concentrates on the concept of vegetative succession and its applicability to managing terrestrial ecosystems in provincial parks. Where appropriate, recommended reference material is incorporated into the body of the text.

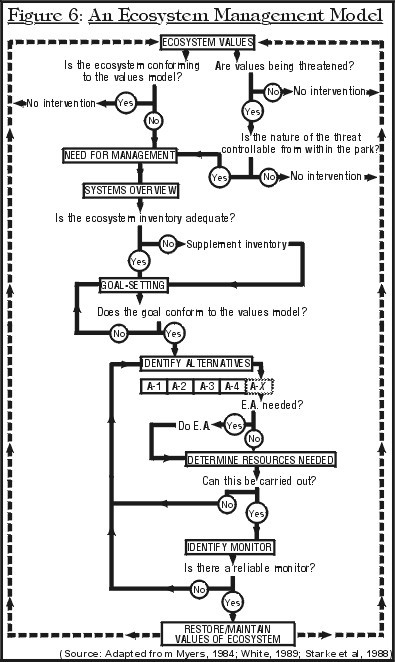

Figure 6 is a model that can be used to help guide park managers. Important stages are elaborated on in subsequent subsections. In this presentation, non-utilitarian values will take some precedence over utilitarian values.  To begin using the model, there must be an input against which ecosystem values will be gauged. This input can be in a past (requiring restoration) or a present (requiring maintenance) tense. To justify a need for management action, there are several fundamental questions a manager must ask. For example, if utilitarian values are taking excessive precedence (actual non-conformity), or the ecosystem(s) is/are being threatened (potential non-conformity), then there is a need for active management. Passive management (i.e. leaving the ecosystem(s) alone) is the only other alternative, but will require re-assessment over time (the dashed line). If the nature of the threat is external (e.g. ozone depletion) and beyond the direct control of the manager then passivity is also justified. A systems overview is necessary before the particular goal can be delineated. This overview must consider the ecosystem inventory and if there is adequate information upon which to base a realistic goal. For example, if there is no comprehensive species inventory, then this should be done first. A goal for that ecosystem can not be set if there is no reference point. Or more simply: one needs to know what one has before one can know what one wants. A good ecosystem inventory generally includes floral, faunal, edaphic (soils), geological, and climatological site factors. Attracting student groups, professional researchers, and local naturalist clubs can help realize a more complete inventory. Once the inventory is deemed adequate, then a goal can be set. This goal must then be assessed in terms of relative ecosystem values to ensure its conformity. It would be a gross managerial error to set and achieve a goal that does not remedy the initial conditions that created the need for the goal. This 'query-to-conformity' acts as an early control mechanism that helps ensure desired results. Once the conformity of the goal has been verified, alternatives that achieve the goal can be considered. The number of alternatives is essentially only limited by knowledge and creativity. For each alternative, it must be decided if an environmental assessment (E.A.) is needed. This will not always be the case. Next, the resources that are required must be pinpointed as precisely as possible. It should be stressed that this does not refer to the physical resources of the park, but rather to the managerial resources of time, labour, money, and equipment. It is these resources that are limited by some of the obstacles discussed in Section 2. If it is determined that it is impossible to execute an alternative, then another alternative should be chosen. If all alternatives are deemed inappropriate to some extent on the basis of resources needed, then the least inappropriate option should be chosen. It may be argued that an environmental assessment will be a waste of man-hours if the alternative that necessitated it is subsequently negated by unavailable resources. Any environmental assessment will, however, contribute to a better awareness of the park and its ecosystems and will thus, regardless of immediate application, be of value in the long term. Finally, a monitor must be identified that can be checked intermittently to ensure that the managerial actions have been successful in maintaining or restoring the values of the ecosystem(s). This monitor can be biotic (floral, faunal) or abiotic. If it is floral, for example, it can be a particular species or community, and can be deemed a viable monitor by either its presence or absence, When the monitor has been identified, the alternative can be acted upon, ultimately restoring or maintaining ecosystem values. It must be remembered that over time sites/systems will change according to successional trends, and so will eventually require another evaluation in terms of conformity or threats. It is an ongoing process. Much of this decision-making is based on subjective evaluations on the manager's part. It is thus obviously important that a manager must first have a solid ecology background so that there is an informed subjectivity to these evaluations.

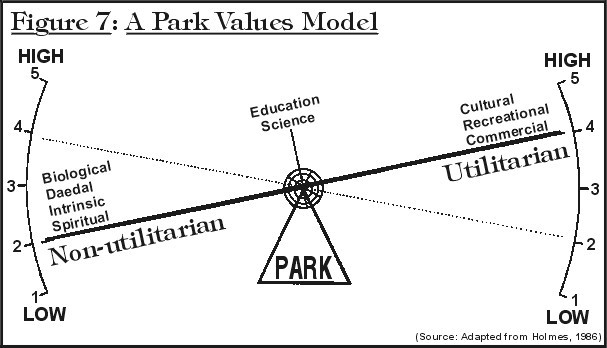

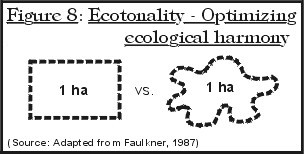

The value of parks has often been assessed anthropocentrically. These values can be said to be use-oriented or utilitarian and, in the case of parks, divisioned as either recreational, commercial, or cultural. Cultural value is not typically an immediate expression of utilitarianism, like recreational or commercial value, but rather a value expressing a celebration of past use. The dominance of utilitarian value in human thinking has resulted in much destruction and overall deterioration of the environment in general, so much so that it arguably threatens the existence of all biota. Human activity is based on use, a time-honoured paradigm. Protection essentially means protection from people, but this is compromised in all parks since "parks" (Recall MNR Avenue, Table 1) are essentially for people. At best, parks try to balance off the utilitarian and non-utilitarian values (See Figure 7).  Non-utilitarian values can be divided into four categories: biological (life-support), daedal (varietal species diversity (number of species), equitable species diversity (relative number of species), habitat diversity, habitat asymmetry), intrinsic, and spiritual. Because these are difficult to measure, they have often taken second place to those that are quantifiable. It is difficult to compare the spiritual value of a forest to the economic value of lumber, for example. Education and science, of necessity, fall in the middle and are unaffected by any shift in the values model. Though they are utilitarian, they are important from a non-utilitarian viewpoint. Interpretation and education are vehicles for helping people understand the importance of the biological, and particularly daedal, values. Since humankind has evolved to a state where technology has the capacity to completely destroy the environment and technology is essentially the application of science, science is one important tool for learning how to mitigate this destruction. The relativity of non-utilitarian vs. utilitarian (or ecocentric vs. anthropocentric) values can be used to quantify the values that (should) dominate particular park classes. Recreation parks thus have a 1:5 value ratio and Nature Reserve parks a 5:1 value ratio. An "Ecological Reserve" would have a 5+:0 value ratio, and Crown land (often reserved for commercial timber and mineral harvesting) has a 0:5+ value ratio. From the values model it is obvious that a 5:5 ratio is impossible. It follows then that a 3:3 value ratio, that Natural Environment parks apparently achieve, is also impossible. Natural Environment parks should thus possess a 4:2 value ratio, where the non-utilitarian takes some precedence over the utilitarian. Wilderness parks would have a 4.5:1.5 ratio, Historical parks a 2:4 ratio, and Waterway parks 2.5:4.5 ratio. Stability, the capacity to withstand stresses, is maintained by rates of energy flow, biochemical cycling, and species diversity (Miller and Armstrong, 1982; Smith, 1980; Faulkner, 1987). Species diversity is proportional to habitat diversity. To maintain or restore daedal values, a manager should attempt to maintain an optimum diversity of habitats and communities. Flows and cycles are linked to biological value. Maintaining diversity greatly reduces threats to the continuity of flows and cycles, and since species and habitats can be directly influenced by managers, and cycles and flows only indirectly through species and habitats, the manager should focus on daedal values. Diversity is also linked to intrinsic and spiritual values, and these too can be optimized through species and habitats. Diversity of producers (plants) determines to some extent the diversity of consumers (animals). Habitat diversity spans both of these. By maintaining diversity in vegetation one also maintains faunal diversity; by maintaining habitat diversity, one maintains floral diversity. Habitats that are asymmetrically arranged (i.e. of varying densities in vegetation) are more diverse than symmetric ones. Symmetry is largely a product of human re-organization, such as evenly spaced rows in a plantation.  One aspect of habitat asymmetry is the concept of 'edge' or ecotonality. Ecotones are ecosystem interfaces such as shorelines, forest edges, or even roads. These areas contain the greatest diversity of species and offer the best locations for assessing this. The value of edge is widely known: experienced hunters and birdwatchers will be found by forest clearings, and good fishermen along shorelines. Ecotonality optimizes ecological harmony (See Figure 8) and should be considered in maintaining diversity, particularly in terms of asymmetry. Note that the land area of the two ecosystems in Figure 8 is the same. The globular system, however, has the greater perimeter/ecotone.

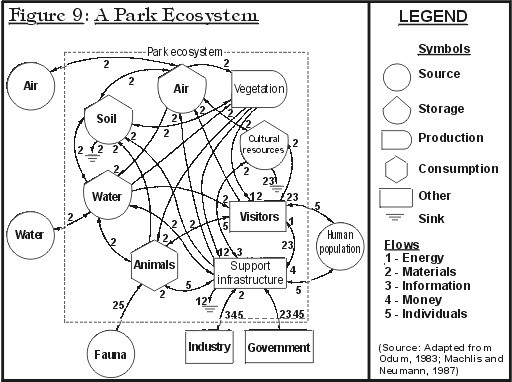

Ecosystems are arbitrary units of nature that include flora, fauna, and abiotic components such as climate, air, moisture, and drainage. More importantly, they are characterized by a finite set of inter-relationships among the components. The arbitrariness of their boundaries becomes obvious when one considers that the biosphere, a lake, or a teaspoon of peat can all be ecosystems (Francis, 1988). Hence, an ecosystem can be widely varying in size depending on the objectives of the manager (Franklin, 1978). Ecosystems can be broken down into communities, such as a conifer stand in a forest, which in turn are composed of species. Vegetative systems tend towards maturity over time, ultimately producing a self-perpetuating "climax" community until acted upon by a disturbance (Faulkner, 1987). They can not be destroyed; only changed. And they will change regardless of human intervention. Long-term trends in change (of site conditions and species composition; brought about by "pioneer" species that prepare the site for different species) are called successional changes. Succession highlights the dynamic character of ecosystems and is a particularly important concept for those who propose to manage, maintain, or restore natural landscapes (Franklin, 1978).  Treating a park as an ecosystem can be used for a systems overview of threats (See Figure 9). It accentuates a few points that park managers should keep in mind. The dashed boundary is emphasizing an open system. It interacts with super- and sub-systems, each of which could also be 'the system'. It is an arbitrary boundary. Inputs to the system are useful in identifying sources of threats and assessing the ability to control them. Generally, air and water threats can not be controlled from within the park because a manager simply has little influence over air currents and water cycling. The inputs also apply to any subsystem within the park. The various flows indicate relationships. Values accompany human individuals.

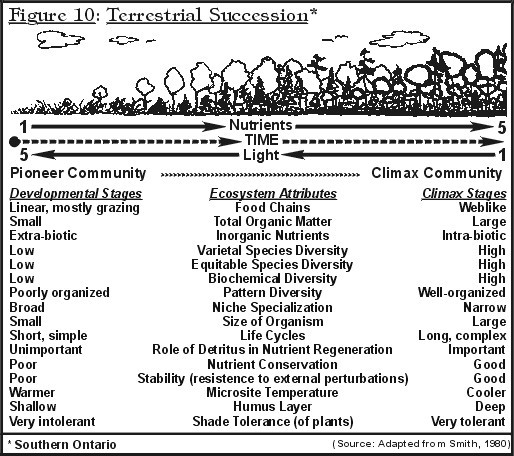

The entire land base of a park, except concrete and asphalt, is always in some stage of succession (See Figure 10). Time links it (via bold-dashed line) to the management model. Succession, in this case, takes place at one location over time with variations on successive combinations of species, depending on latitude and drainage. It is a continuum, with increasing diversity (and complexity) over time. Even greater diversity can be achieved by maintaining a variety of stages. This variety will determine ecotonality. Disturbances (e.g. fire, tornado, logging) 'set back' or renew the process.  The goal for a particular ecosystem will be either natural succession, accelerated succession (as the Pinery created; recall Foreword), normal/accelerated succession to a particular stage, setback to an earlier stage by simulating a disturbance, or maintenance at the particular stage by regular disturbances. Habitat requirements for particular faunal species should also be considered (based on inventory) in setting these goals. (See: Martin, A.C., H.S. Zim, and A.L. Nelson. American Wildlife and Plants: A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits. New York, NY: Dover, 1951.)

Monitoring is an important aspect of management by succession. It is the means by which the desired stages of succession are determined or maintained. A monitor can be useful by its presence or its absence. Presence of a particular species would indicate an existing stage, while absence would be indicative of an earlier or later stage. (Note: usually a particular community offers a better appraisal than one species). It is this presence or absence that should be 'monitored'. Some species of plants have very precise needs (a component of niche specialization), and are thus very selective or restricted in the sites and successional stage(s) at which they can exist. They can function as indicator species of site types, as well as for successional stages and diversity (See Table 2). Table 2: Monitor Species [Top] Synecological requirement of forest species for moisture(M), nutrients(N), heat(H), and light(L), in relative value from 1(least) to 5(greatest).

(Source: Adapted from Faulkner, 1987.) Light and nutrient availability are transcribed onto Figure 10. Very high values represent the factors most limiting upon the species. Species with high light values indicate pioneering stages; species with high nutrient values indicate climax stages. These two factors are directly linked to succession. An abiotic monitor, such as temperature, depth of the humus layer, or soil acidity, may also be used. CONCLUSION [Top] Ecology is implicitly holistic, and a vital discipline for park managers. Ecological values must take precedence to ensure diversity, stability and, ultimately, sustainability of park ecosystems. This must be the super-ordinate goal of every superintendent, but especially for superintendents of Natural Environment, Wilderness, and Nature Reserve parks. Natural Environment parks, with their greater present emphasis on utilitarian values, are most in need of management with ecosystem concepts like succession in mind. A management model based on clearly delineated ecosystem values can help assure an ecosystem management orientation. Overcoming the obstacles presently inherent in the parks system will hasten the ubiquitous realization of this imperative. LIST OF REFERENCES [Top]

In May, 1988, the provincial government announced its new parks policy. The policy includes increased protection for wilderness and nature reserve parks and adds new parks to the provincial system. The parks system will increase by 53 new parks by May, 1989, to a total of 270 provincial parks. Within the system there are six classes of parks: wilderness, nature reserve, historical, natural environment, waterway and recreation. In all classes of parks in the provincial system, the parks policy itself prohibits mining activity, commercial hydro-electric development and logging (except in Algonquin and Lake Superior parks where logging is permitted to continue). In addition the policy will eliminate, through a transition period, commercial trapping, commercial wild rice harvesting, and most commercial fishing. Under the new policy there may be some changes for some parks users. In the interest of fairness an implementation schedule has been developed which includes a transition period for changes. The implementation schedule emphasizes the importance of park management planning as the key mechanism for encouraging broad public consultation in developing the pattern of uses, facilities and services for parks. The principles for management planning safeguard the integrity of a system that protects natural and cultural heritage features and ensures a variety of outdoor experiences is available to the public. Management planning involves the public by providing opportunities to review and comment on information developed at several stages in the process. The public reviews background information prepared by the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) on a park. Then MNR provides issues and policy options on protection, development and use of resources in parks for public review. Next a preliminary plan is developed for a park and released for public comment. At the end of this public consultation process the ministry prepares an approved plan for a park. This management plan is reviewed periodically or after 10 years, affording another opportunity for public involvement. The ministry uses a variety of techniques including public meetings, open houses, drop-in information centres, tabloid publications and other means for seeking public input into management plans. This fact sheet outlines the transition period for changes and the role of park management planning in the process. o The ministry policy on sport fishing in provincial parks has not changed. o Angling continues to be permitted in all classes of parks except where fish sanctuaries are established. Fish sanctuaries protect important species of fish, primarily spawning fish at certain times of the year. o In all wilderness and nature reserve parks hunting will not be allowed as of January 1, 1989. o In all wilderness or nature reserve zones within waterway, natural environment, historical, and recreation parks, hunting will not be allowed as of January 1, 1989. o Hunting continues in parks legally established before 1983 where permitted by regulation in selected parks, except in wilderness and nature reserve parks. This policy on hunting in waterway, natural environment, historical and recreation parks may change on a case-by-case basis when park management plans are established or reviewed. (See Appendix A) o In waterway, natural environment, historical and recreation parks hunting will continue by regulation in selected parks created since 1983 until decisions are made during the park management planning process. (See Appendix B) o In proposed new waterway, natural environment, historical and recreation parks hunting will be allowed by regulation in selected parks, until decisions are made during park management planning. (See Appendix C) o In all provincial parks the policy calls for hunt camps to be phased out of parks. Except for wilderness and nature reserve parks, hunt camps will be allowed to remain until park management plans are established or reviewed. o A transition period for changes to hunt camps is outlined below:

o Commercial fishing and commercial bait fishing will not be permitted within provincial parks, except in lakes that are not wholly contained within provincial park boundaries and in waterway parks where these activities will be permitted until addressed during park management planning. o The licences of existing operations in water bodies wholly contained within park boundaries will be phased out within 21 years or when a licensed operator retires or dies, whichever is sooner. o In wilderness parks, tourist operators may continue to be allowed to bait fish in designated water bodies. These operators must be licensed and must supply the bait fish for in-park use by clients. o In all provincial parks, commercial trapping will not be permitted, except by licenced status Indians enjoying treaty rights. o commercial trappers will be phased out within 21 years or when the trapper retires or dies, whichever is sooner. o New traplines will not be established in provincial parks. o Where a trapper's licence lapses, it will not be renewed. o The transfer of existing traplines inside provincial parks will only be allowed between or to status Indians. o Only status Indians are permitted to assist status Indian trappers. o In nature reserve parks, tourism operations will not be permitted. o In wilderness parks, existing tourism operations, including existing fly-in operations, will be allowed to continue. Decisions on relocation and expansion of existing operations and decisions on the development of new operations within a park will be made when park management plans are prepared or reviewed. o In natural environment, waterway, historical and recreation parks, existing tourism operations, including existing fly-in operations, may be permitted to remain. Decisions to allow these operations to continue, to expand or to relocate within parks and decisions to allow new development will be made during park management planning. o The new parks policy includes measures that cover mechanized travel in all classes of parks in the system. o In nature reserve parks, motorboats, snowmobiles and all-terrain vehicles will be restricted to access zones in the parks. Restrictions will be placed on the size of motors on boats. o In wilderness parks, snowmobiles, all-terrain vehicles and motorboats will be restricted to access zones. Tourism operators may be permitted to use motorboats outside access zones, as determined through park management planning. Restrictions will be placed on the size of motors on boats. o In waterway, natural environment, historical and recreation parks, decisions on mechanized travel will be made during park management planning. Restrictions may be placed on the size of motors on boats. o In all parks, cottages on leased lots and on lots covered by land use permits will be phased out at the end of 21 years, beginning January 1, 1989. In Algonquin and Rondeau provincial parks cottages will be phased out by the year 2017. o The province will acquire cottages on patented lands as funds permit and on a willing seller basis. o In all parks, commercial wild rice harvesting will not be permitted, except by status Indians enjoying treaty rights. o The operations of existing commercial wild rice harvesters will be phased out within 21 years or when the harvester retires or dies, whichever is sooner. o New mining activity, including prospecting, staking claims and the development of mines, will not be permitted in provincial parks. o In all provincial parks, logging is not permitted except in two cases. Logging will continue in Algonquin Park under the Algonquin Forestry Authority and in Lake Superior Park. o No new commercial hydro-electric developments will be permitted in any park. o Status Indians enjoying treaty rights will be permitted to carry on traditional natural resources harvesting activities in accordance with the terms of their treaty within within provincial parks in their treaty areas. Accordingly such status Indians will be permitted to carry on those activities in certain circumstances. The details of these circumstances will be the subject of further discussion and review. o In wilderness parks, licensed hunters may hunt in the park if they are guests of existing commercial hunt camps in the park that are owned and operated by status Indians. Decisions on relocation and expansion of existing commercial hunt camps and decisions on the development of new operations within a park will be made when park management plans are prepared or reviewed. o With the addition of 53 new parks by May 1989, Ontario will have 270 provincial parks covering 6.3 million hectares. This represents six per cent of the total land and water base of the province. o More than 80 per cent of the lands and waters in the parks system will be in wilderness and nature reserve parks and in wilderness and nature reserve zones in waterway, natural environment, historical and recreation parks. o The complete system of 270 parks will have four historical parks, 31 waterway parks, 76 recreation parks, 67 natural environment parks, eight wilderness parks and 84 nature reserve parks. APPENDIX A Provincial Parks Regulated Before 1983 That Will Permit Hunting

* Indian owned and operated goose hunt camps on Hudson Bay. APPENDIX B Provincial Parks Regulated After 1983 That Will Permit Hunting

APPENDIX C Post-1983 Provincial Parks Not Yet Regulated That Will Permit Hunting

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||